By David Collings, Sharon Collard and Jamie Evans

Back in July we published a review of bank card gambling blockers – a feature that allows a debit or credit card customer to block their account or card from being used for gambling transactions. Working with GambleAware, we evaluated the potential for these blockers to help those who want to control their gambling.

Our review brought together bank data on customer use of blockers; discussions with treatment providers, firms and regulatory bodies; and, crucially, insights from over 100 interviews and surveys with people who have lived experience of gambling. It showed that blocker technology works and can help people control their gambling spend, but card blockers need to be more widely available than is currently the case. And, where offered, their design should incorporate elements of ‘positive friction’ in the form of ‘cooling-off’ periods.

Making gambling blocks more widely available

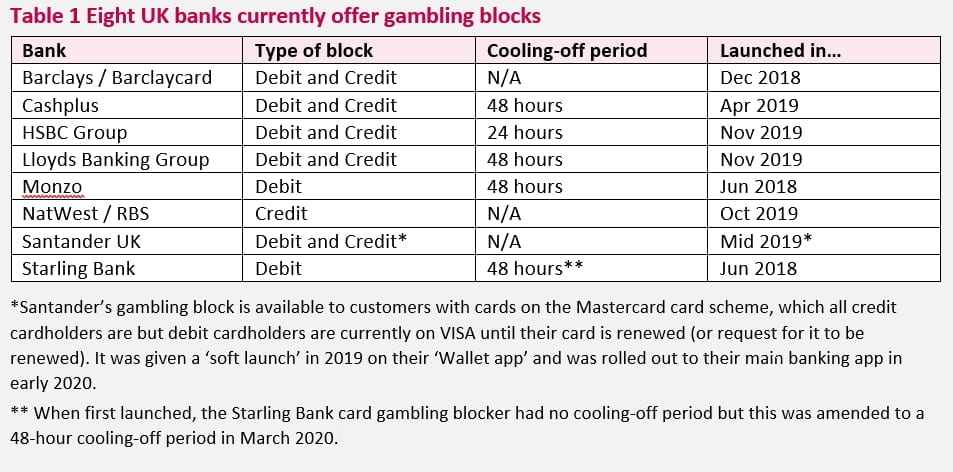

At the time our report was written, eight firms advertised and offered blockers to their customers either on credit cards, debit cards or both. These include five of the nine largest banks and building societies in the UK – Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds, Royal Bank of Scotland Group and Santander – together with three other banks – Cashplus, Monzo and Starling.

We estimated that gambling blocks on debit cards are available for roughly 60% of personal current accounts (around 49 million accounts) and at least 40% of credit card customers (roughly 26 million cards). But if Santander and the Royal Bank of Scotland Group were to offer gambling blockers to all their debit card customers, we estimate that blockers would be available for around 90% of current accounts (equivalent to 70 million accounts – 22 million more than at present).

Making sure gambling blockers include ‘positive friction’

Increasing availability of these blocks isn’t enough on its own. Our findings show that blockers need to include ‘positive friction’ in the form of ‘cooling-off’ periods – to encourage time and reflection before someone can gamble again – in order to be effective.

As the table above shows, five of the eight firms offering blockers included a cooling-off period – a period after a customer disables the block before they can gamble again – while the remaining three blockers could immediately be toggled on and off, meaning they functioned more like a light switch than a lock.

But this is a fast-changing landscape. In September Barclays announced it is introducing a 72 hour cooling-off period to its gambling blocker, responding to customer feedback about the positive impact of such a delay, making it the first bank to introduce a cooling-off period off this length. This customer feedback echoes findings from our research, where nearly 60% of respondents with lived experience of gambling felt that a cooling-off period should be longer than 48 hours.

In fact, the message from those affected by gambling was clear: the more positive friction that can be built into a bank blocker, the better. Our research also explored other examples of positive friction that could be beneficial, including making gambling blocks the default on new bank cards, or automatic alerts for third parties such as a friend or family member related to gambling spend.

More to be done

Our interviews with banks highlighted three main motivations for developing and implementing gambling blocks: ‘soft’ pressure from regulators; evidence of customer harm from gambling; and market ‘peer pressure’ as other banks launched gambling blocks for their card customers.

We therefore reiterate our call on the Financial Conduct Authority as part of its forthcoming guidance on the fair treatment of vulnerable customers to recommend that gambling blocks are standard on all credit and debit cards and require customers to wait at least 48 hours between turning off the blocker and being able use that card to gamble.

Finally, introducing gambling blockers shouldn’t be seen as ‘job done’ for banks and building societies – there is much more work to do and the purpose of our three-year MAGPIE research programme is to help progress that agenda. Similarly, other organisations beyond banks still need to be taking robust action to reduce gambling harms.

This blog was originally posted on the Money and Mental Health Policy Institute blog. Read the original post here.